Print over Pinterest - Andrée Putman

We are starting strong with a deep dive into the career of notable interior designer Andrée Putman, from the 1997 book, Andrée Putman, written by Sophie Tasma-Anargyros.

Putman’s work has stuck with me as long as I have been immersed in the world of design - so, since my mother dragged me to my first furniture showroom at the ripe age of 5.

Putman’s disregard for traditional design rules, paired with her attention to the evolution of modern lifestyles, formed an aesthetic that was unmistakably her own. Decades later, her work remains immediately recognizable.

Like most creative women, Putman is hard to define in a single sentence. An interior designer, curator, fashion editor, and furniture designer, to name a few of her talents. Putman began her career in fashion and publishing before turning to interior design later in life. While working as a messenger for the journal L’Œil, she encountered artists, writers, and thinkers who reshaped her understanding of modern culture. She soon began writing about interiors and became involved with Prisunic. It was in this accessibly priced French retail chain that she challenged the established idea that style equalled elitism. Like many icons of the mid-century period, she was driven by the desire to make art and design accessible through mass distribution. This period marked her belief that modern design could be produced industrially without losing its intelligence or integrity.

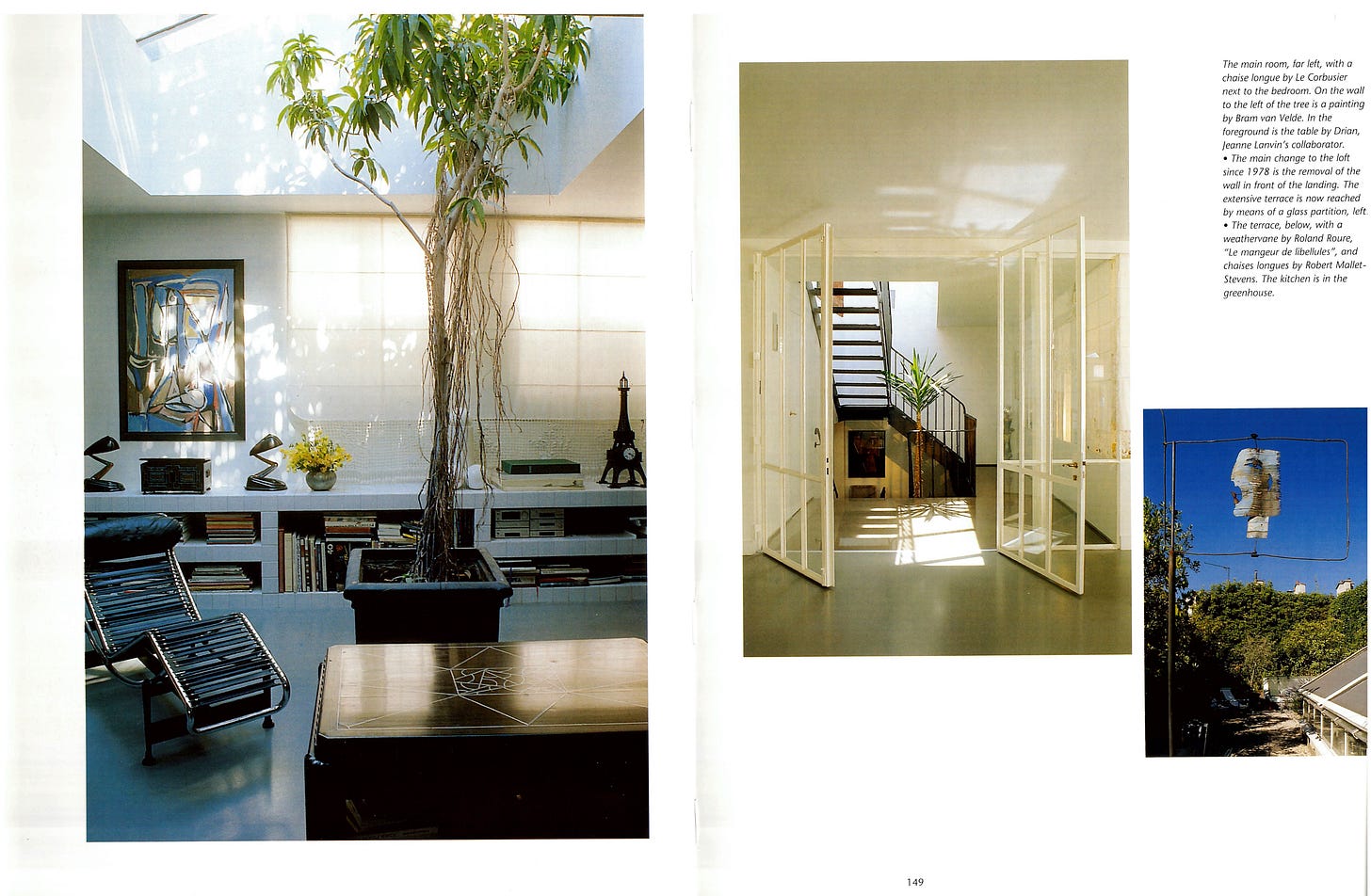

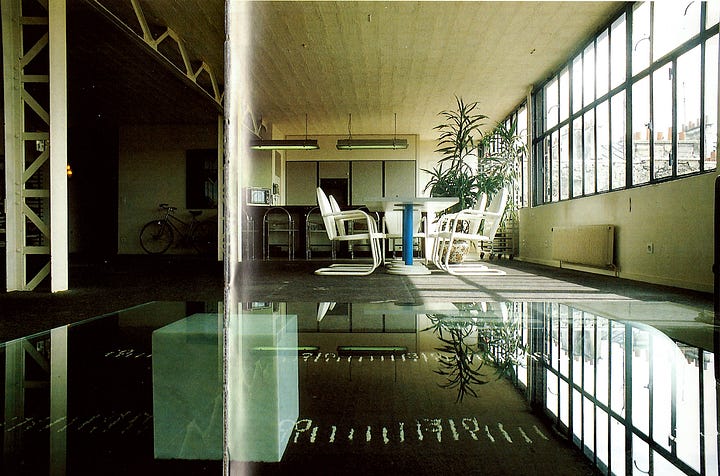

Putnam’s Parisian loft, 1980s.

Her apartment was, unsurprisingly, filled with iconic pieces, including a black leather Le Corbusier LC4 lounge chair, Thonet Model 209 bentwood armchairs, and a variety of Eileen Gray rugs.

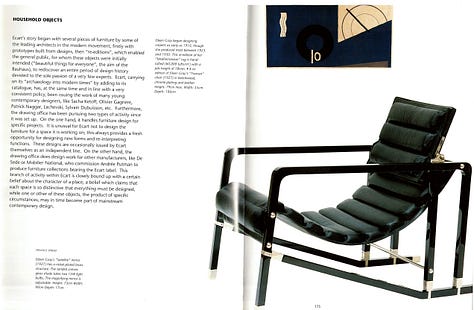

She founded Écart International in the late 1970s, a furniture showroom that positioned itself as a pioneer in what it called an “archaeology of modernity”. Aiming to reissue furniture and objects from historical creators of the early 20th century by obtaining the licensing and producing under the Écart label. She played a key role in reviving interest in modernist designers such as Eileen Gray, Jean Prouvé, and Pierre Chareau, helping to cement their place in design history.

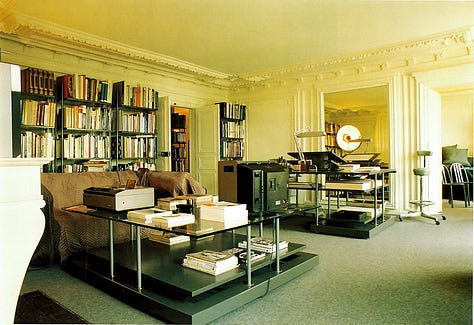

Various pieces designed and reissued at Écart;

Écart showroom, designed by Putman (1991).

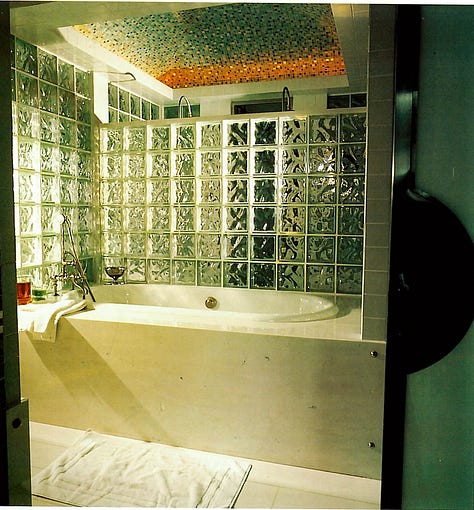

Putman was known for her use of black and white, specifically her iconic checkerboard mosaics.

“I like the beautiful and the useful, and even more the beauty of the useful.” Putman once said.

Raised within the bourgeois interiors of her childhood, Putman developed an early aversion to excess, becoming a self-described minimalist. “Aged 15, I told my mother I wanted to clear my bedroom of all the objects that crowded it”. Putman once recalled.

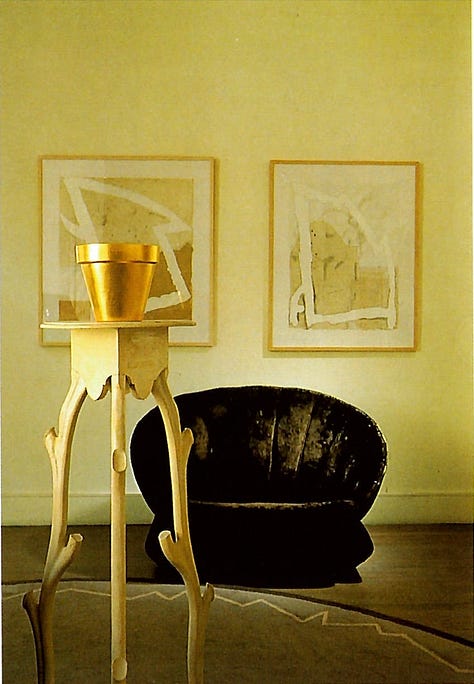

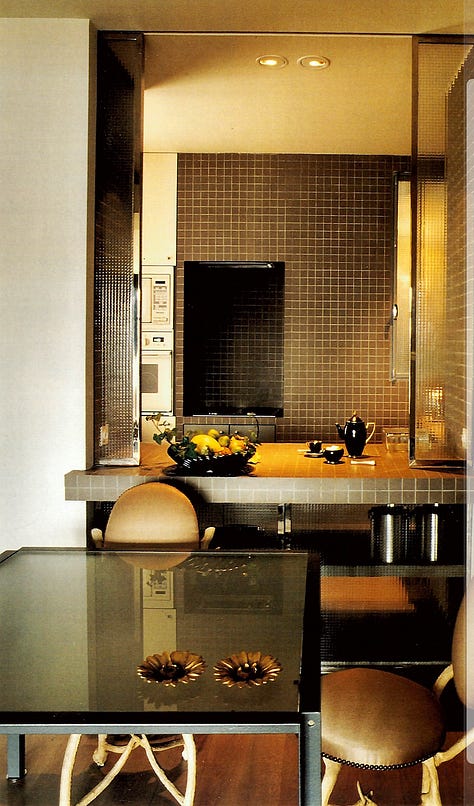

Stan Levy and Colette Bel’s, Paris (1981);

Her residential work somehow never reads as stark minimalism, even though she designed within a neutral colour palette. There is warmth and character present, despite her taste being rooted in simplicity.

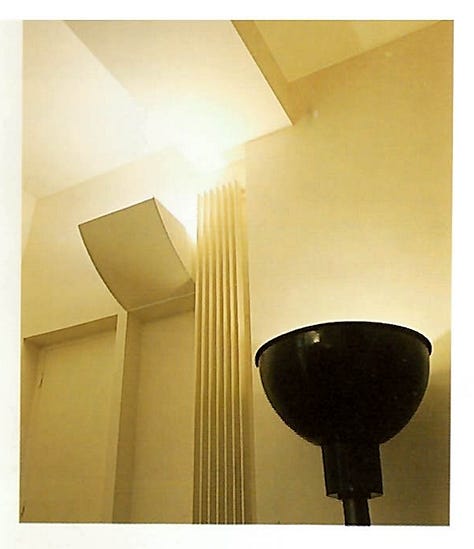

Various residential projects Putman designed;

Putman also designed countless commercial spaces. She consistently returned spaces to their essential state, removing excess to focus on structure, light, and proportion.

Emptiness, for Putman, was not absence but possibility. Her interiors often contained only what was strictly necessary.

As her reputation grew, Putman was entrusted with overseeing the renovation of the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Paris in 1992.

Light played an essential role in her work. Natural light, in particular, often evoked childhood memories. Putman treated it as a material in its own right, filtering, reflecting, and shaping it through glass, mirrors, and architectural details.

Other various corporate and commercial spaces Putman designed;

Putman’s work has stayed with us not because it demands attention, but because time rewards it. In a world increasingly driven by excess, Putman’s work offers something rare: permission to slow down, and to trust that quiet decisions can leave the strongest impression.